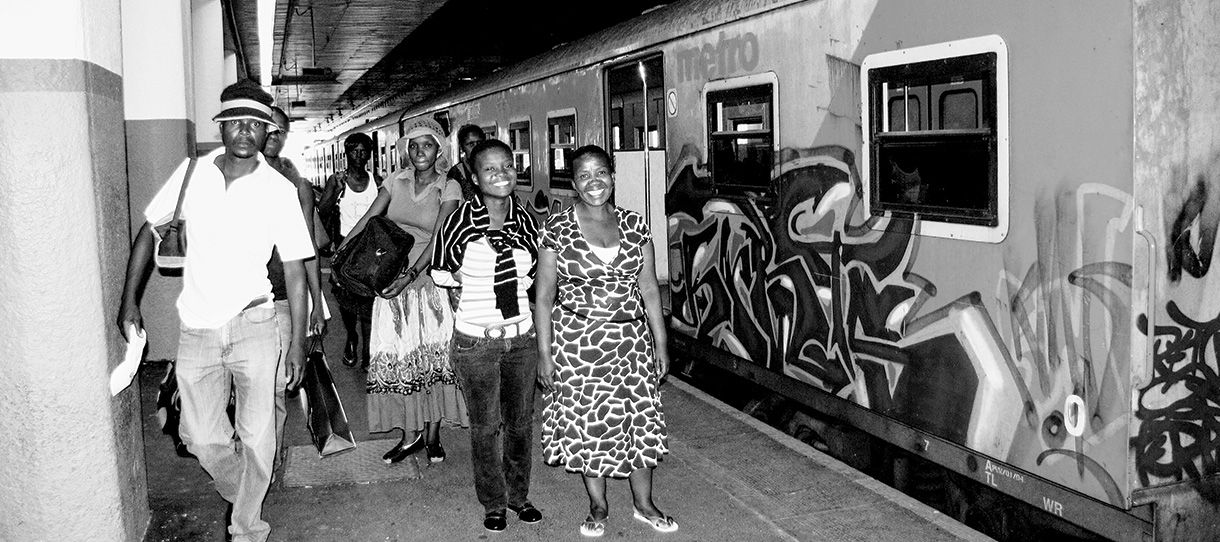

At the end of the year thousands of people leave the City of Gold to return to their homes and families far away. Elizabeth Donaldson takes the journey with them...

It’s early evening and passengers on the northbound train to Musina are pouring through Johannesburg’s Park Station. Endless red, white and blue nylon bags march towards the platform: On heads, on backs, dragged by tired children; all filled to capacity with everything from rice and oil to blankets and boxes of fake Nike trainers. Expressionless travellers file through the gates as the guards scream, shout, prod and push them like unruly cattle.

“You don’t know where you’re going. Why didn’t you check the board? You people never check the board. You never know what’s going on,” howls the Musina train conductor, his breath thick with brandy.

Passengers spill onto the train, throwing their luggage up the impossibly steep steps and scrambling to find a place to sit. The third class carriages are packed and the air is already stale and sour. It’s hot, and bewildered children wail while adults raise their voices to counter the interference. Amid this chaos, the heavenly quiet of the deserted first class compartments with their smell of old leather and bright, shiny bathrooms is well guarded by the conductor. They will remain empty.

The commotion reaches fever pitch as the whistles blow to announce our departure. Everyone’s nervous. Everyone’s suspicious of everyone else. We’ve all heard of the tsotsis, pickpockets and scam artists, so we find the place where we feel least threatened: Shonas sit with Shonas, old men with old men. Pedi with Pedi, ZCC with ZCC, huddling together, checking and rechecking luggage. I join a cluster of women. One is young and pretty, one is middle-aged with a huge smile and a strange sock on her head, the other is old and stares fixedly out of the window.

“Don’t mind her,” says Sock Lady nodding at the window-gazer. “She hasn’t said a word to anyone. Miserable cow. Come, give me your bag, there are some troublemakers on board tonight.”

The younger woman nods her head in agreement and hides my bag under the seat behind a blue plastic box.

“Have you got a blanket? It’ll get cold soon.”

”I asked the guard for bedding.”

“The man’s a pig. He’s as drunk as a skunk,” says Sock Lady. I start to laugh.

“He is, isn’t he?”

“Pig. If they don’t bring you bedding, don’t worry I have extra. You can use mine.”

The sock lady says everyone calls her Sis Jean. The young one is called Orinah. (No, it’s not from the Bible. No, she doesn’t know where it’s from. She suspects her parents might have made it up). ‘Miserable cow’, as she is now known, refuses to give her name. She just keeps staring out of the window as if there’s anything to see besides an empty railway track.

Sis Jean is deeply offended. “Huh, we’re going to be on this train for another 17 hours you’d think she’d make an effort. Bloody church people are all the same.”

For those going on to Harare, it’s the start of another day…,and wondering what happened to humanity.

The old woman is wearing a ZCC badge, which Sis Jean refers to as the Zulu Cricket Club.Orinah, lovingly clutching a black leather Bible, tries to put in a good word for the ‘church people’, but Sis Jean’s not having any of it. “You can convert mankind from the waist up and nothing more. From the waist down we answer to only one thing,” she declares.

Poor Orinah opens and closes her mouth like desperate fish. “But Sis Jean, the good Lord…”

“And those bishops of yours flocking to church to watch the choir leaders wiggle their backsides – disgraceful. And don’t tell me it’s not true because you’d be lying.”

Orinah gives up. “Very well, but you can’t tell me you don’t enjoy the hymns. The singing is glorious.” She breaks into a hymn and Sis Jeans joins in. They finish and smile at each other in satisfaction.

As the train starts moving, everyone settles down. Each carriage has an unwritten order; men occupy the back seats with the luggage while women sleep along the walls and on the seats, with the children curled up in the aisles between them. But it’s almost impossible to sleep for the noise and the lack of space. The train lurches into a station every half hour; Hammanskraal, Bela Bela, Naboomspruit, Mokopane, Polokwane, Soekmekaar, Mokhado (although everyone still calls it Louis Trichard pronounced ‘Loose Treshjard’), Mara, Mopane and finally Musina.

“Won’t get much sleep tonight,” Sis Jeans sighs as the throb of music from a sadly incapacitated CD gets cranked up beyond distortion. The former nurse lives in a large four, bedroomed house on the tree-lined streets of a once-fancy suburb of Harare. Her once shimmering blue swimming pool – her pride and joy – is now empty. “It cost too much to maintain and that’s only if you can get chlorine, which is impossible now. I’m thinking of filling it in, but I can’t bring myself to. Who knows, maybe Uncle Bob will step down and I’ll be able to get chlorine again?

Sis Jean has five sons, all university graduates, spread across the globe. “My eldest lives in London. My grandchildren are English now. And why not? The world is a global village now, isn’t it? Look at me. I’m Xhosa living among Shonas with a best friend who’s Jamaican and my grandchildren are English. It’s the future.”

Orinah is from Bulawayo. She’s a poet, but makes a living as a parking attendant at Park Station. “Some days I earn R40; others R100 but no matter what I earn I always save R5. If I can save R5 a day for a year that‘s R1 825. Better than nothing, isn’t it?”

At every stop hawkers emerge from the shadows like ghosts, carrying six-packs of beer to sell though the windows to men deep into serious card games. We see guards at regular intervals: Some serious in neat blues and ties, carrying bedding and making sure no one’s smoking. Others, like the conductor, are blind drunk and grubby. We learn who to avoid and who to ask for water when three bathrooms run dry. Mosquitoes have invaded the carriages in thick clouds, hovering high in the corners when the train comes to a standstill and disappearing miraculously when we start moving again. We settle down for the night.

Sis Jean is reading her two romance novels. One with a blond heroine on the cover staring lovingly at a buff and tanned hero who’s a dead ringer for Ridge in The Bold, and the other with a voluptuous redhead bursting out of a velvet bustier. She switches from one to the other every chapter. “Why do you read two at a time?” I ask, more interested in why she reads them at all.

“Otherwise I get bored. They’re not very interesting,” she explains without looking up.

Unable to sleep I go in search of tea. The dining car is not a happy place. There is no stock and the Formica tables are empty. In fact, the entire dining car is empty except for the tall, thin cook standing forlornly in a corner, smoking a cigarette and staring down sadly at the carcasses of three raw chickens. “Closed until six tomorrow,” he mumbles.

The night passes in a rumble of brakes, mosquito bites and dreams of quiet. At daybreak, everyone starts rushing around as if they were late for church – although there’s still six hours to go before we hit Musina. Sis Jean wants something to eat, so it’s back to the dining car. She raises her eyebrows in disapproval at the cigarette hanging out of the chef‘s mouth. “Good morning. Now put that cigarette out, it’s unhygienic. What can you offer us for breakfast?”

“Eggs and bread,” says the man, throwing his half-smoked Gunston out of the window.

We order food and tea and return to our seats to perch on the pile of blankets and wait for breakfast: Me, Orinah and Jean.

The bush slides past the window. There’s been rain and the river is flowing strongly. The leaves on the mopane trees are a bright, luminous green and the surreal trunk of a baobab marks the horizon. “The upside down tree,” I tell them.

“Really?” Sis Jean looks indignant at the whimsy of it. Ever practical, she explains the many uses of the leaves to me – medicinal and culinary. Talk of food gets Orinah so excited she puts her Bible down and breaks into an animated explanation of an acha dish prepared with baobab leaves.

The train is quieter now. Most of the passengers got off at Polokwane and Makhado, leaving a handful of Zimbabweans with a trainload of luggage to make the final trip to the border. Everyone’s tired and irritable and by the time the train rolls into Musina station and the jostling starts, tempers flare. The third class carriages are a least a kilometre from the platform and passengers struggle across the gravel to the gates. More guards wait to scream, prod and push. Outside the gates, taxis hoot, money-changers haggle and the smell of tripe clings to the air. For those going on to Harare, it’s the start of another day of heat, noise, chaos, bullies and wondering what happened to humanity.

THE END OF THE ROAD

Facts about Musina

- Musina is the northernmost town in Limpopo province, located close to the Beit Bridge border post between South Africa and Zimbabwe. It’s the main entry point into South Africa for African countries.

- Stats SA recorded in August 2017 in its latest Tourism and Migration Survey that almost 31 percent of people who had passed through South African ports of entry in August were Zimbabwe citizens.

- In a feature in the Daily Maverick in mid November, written after President Mugabe had stepped down, Craig Smith, founder of a company of migration lawyers said that, depending on how the situation unfolded in Zimbabwe, either more Zimbabweans would come into South Africa, or those here already would return home. “If it’s non-violent and it presents economic opportunities, we might see some Zimbabweans going back home, and if it turns violent, we might see a new influx of Zimbabweans coming to South Africa,” he said. He believed that Zimbabweans living in South Africa would only leave the country if they could not find jobs here, and that the transition in Zimbabwe represented economic opportunities. But, he added, “Right now it is difficult for anyone to predict.”

Written By: Elizabeth Donaldson

In your comments, please refrain from using offensive language and unnecessary criticism. If you have to be critical, remember – it must be constructive.

0 Comments