It is a relationship born of a natural affinity with a sport that exhibits time-honoured values and a dynamic spirit. Six decades into its partnership with yachting, Rolex is the committed supporter of the some of the world’s most prestigious yacht clubs, races and regattas.

Rolex can trace its connection with the sea back to the company’s origins in the early 1900s, when founder Hans Wilsdorf envisaged a pioneering watch that would be robust, precise and reliable. The strength of this association would be cemented by the feats of three extraordinary individuals, which helped confirm Wilsdorf’s perceptive understanding that increasingly active lifestyles demanded a wristwatch chronometer that was accurate, self-winding and, significantly, waterproof.

The 1960s was a period that added considerable impetus to the sport of yachting, and particularly the discipline of offshore racing. The challenges faced by today’s sailors may appear a world away from those encountered in the middle of the last century, but those heading to sea and out of sight of land for extended periods are still inspired by the characters and achievements of that era. Advances in technology, materials and design continually improve navigation, fitness for purpose and comfort, but the open ocean remains an unforgiving environment.

Until the beginning of the 20th century, offshore racing had been the preserve of large yachts with paid crew. The 635-nautical mile Newport-Bermuda Race, first held in 1906, became the catalyst for the 605-nm Rolex Fastnet Race (founded in 1925) and opened the door to racing offshore in yachts of 10 metres (30 feet) and upwards. When the 628-nm Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race was founded in 1945, the discipline had truly come of age. Other races, of about 600 nm, would follow, including the Rolex China Sea Race in 1962, the Rolex Middle Sea Race in 1968 and the RORC Caribbean 600 in 2009. Passion was the key element in the early editions of these races, with small numbers of enthusiastic participants.

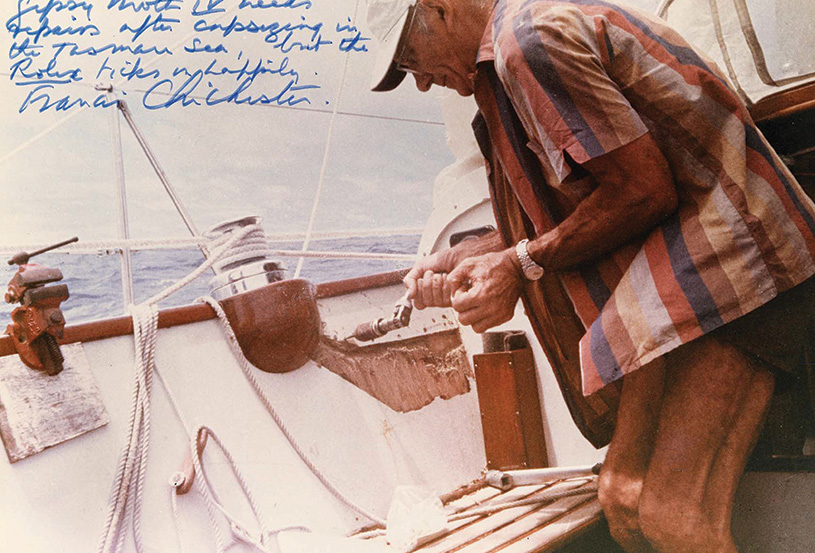

“Gipsy Moth IV needs running repairs after capsizing in the Tasman Sea, but the Rolex ticks on happily.”

Sir Francis Chichester

THREE LEGENDARY OCEAN FEATS. ALL ACCOMPANIED BY A ROLEX

A series of accomplishments would add the allure of adventure and testing oneself to the simple concept of competition, thereby broadening the appeal of offshore sailing. In 1960, the first solo transatlantic race was won by British yachtsman Sir Francis Chichester. Such was the success of this inaugural race that four years later it was held again with more than twice as many participants. Chichester would finish second on this occasion. Spurred on to greater heights, he then set about proving it was possible to sail solo around the world from west to east in a time faster than the three-masted clipper ships of the 19th century.

Setting off in 1966 aboard his 16-metre (55-foot) ketch Gipsy Moth IV, Chichester counted among his ‘crew’ a sextant and a Rolex Oyster Perpetual chronometer, which absorbed the same drenching and scrapes as him. In one captioned picture from the voyage, he noted that “Gipsy Moth IV needs running repairs after capsizing in the Tasman Sea, but the Rolex ticks on happily.” After 226 days, including a stopover in Australia, Chichester returned to Plymouth, United Kingdom, having rounded the three great Capes: Good Hope, South Africa; Leeuwin, Australia; and, the Horn, Chile. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for “sustained endeavour in the navigation and seamanship of small craft”. His epic feat, undertaken at an age when most are considering retirement, inspired still greater achievement. The clipper route, embraced by Chichester, is the favoured course followed by the most challenging round-the- world yacht races, all of which came into being after his venture.

The first of those races was established only a year later. Nine yachtsmen took on the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race, the first non-stop, single-handed, round-the-world yacht race. The level of the unknown that such a voyage presented then is difficult to comprehend in this age of digital mapping, mobile communication and satellite navigation. More was understood about heading into outer space.

The pioneering route undertaken by Sir Francis Chichester in 1966/67

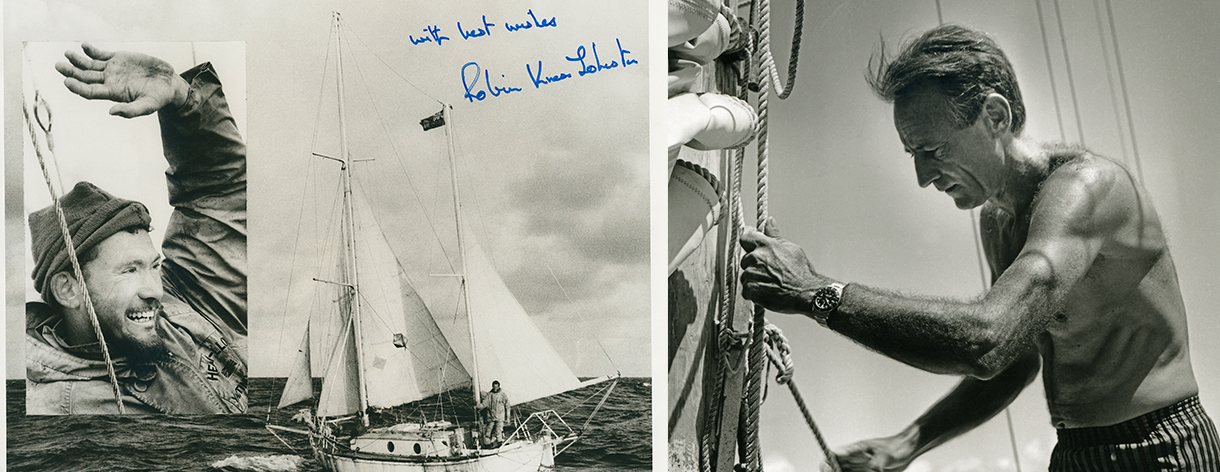

When the French sailor Bernard Moitessier and British yachtsman Sir Robin Knox- Johnston set off to prove it was possible for man and machine to circle the earth, few believed they would succeed. Like Chichester, they had to rely on their seamanship and determination to survive whatever the oceans threw at them. Conserving resources and protecting their yachts were key concerns. So, too, was navigation, which remained reliant upon the time, the sun and the stars to plot position with any degree of precision.

Of the nine sailors to embark on the challenge, only one completed the full course. Moitessier looked capable of completing the task and in the fastest time, but chose to abandon the contest, continuing east towards the Cape of Good Hope for a second time rather than heading north once he had rounded Cape Horn. Moitessier would go on to cover some 37,455 nm before coming to rest in Tahiti, the longest non- stop passage by any yacht. Knox-Johnston persevered with the quest, overcoming the adversities, privations and solitude, arriving back in Falmouth, UK, in April 1969, some 312 days after his departure. As the winner of the Golden Globe, he entered the history books as the first person to successfully circumnavigate the planet solo, non-stop.

Sailing prowess aside, Knox-Johnston and Moitessier were both indebted to the resilience and reliability of the Rolex Oyster as an essential tool among the navigational aids on their voyages. Originally bought for diving, Knox-Johnston laid great store by the characteristics of his Rolex: “It was strong enough to take a bashing and was predictable, which was what I really needed for navigation, particularly when taking sights on deck. It was a good, reliable, trustworthy watch. Through all the punishment it received it just kept going. It was still working perfectly when I got home, which says it all.” Writing to Rolex in 1969, Moitessier advised that: “Your watch has done me great service – it never left my wrist, even during difficult manoeuvres. Serving me throughout the trip as a navigational chronometer, it was one of the important elements of this voyage, thanks to its precision and its robustness.”

Sir Robin Knox Johnston & Bernard Moitessier

ROLEX: THE COMMITTED PARTNER OF LEADING OFFSHORE RACES

Given this background, it is perhaps only natural that Rolex would seek to partner yacht clubs and events that foster the endeavour and skills exhibited by the sport’s pioneers. Rolex stepped offshore to secure relationships with the world’s top 600-nm races and the organizations behind them. Stringent examinations of sailing skill and human endeavour, these classic contests and their organizing clubs have, like Rolex, been defined by a spirit of adventure.

The most famous are the biennial Rolex Fastnet Race, run by the Royal Ocean Racing Club (RORC), and the annual Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race, launched by the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia (CYCA). Widely regarded as northern and southern hemisphere equivalents, and both supported by Rolex since the beginning of the 2000s, they are on every offshore sailor’s wish list.

The primary focus for all participants at these races is, first and foremost, to finish. If one has an eye on winning, the focus is doing so in the shortest possible time. Plotting the correct route, maintaining the optimum speed in the prevailing conditions and time-management of resources are essential components of a successful voyage, just as they were for the pioneers of 50 years ago. Crews have to manage their strategy and resources according to the potential and characteristics of their boat. There is no room for complacency, nor error in judgement, in the pursuit of victory. Every decision has to be accurate and timed precisely. Taking care of the minute details remains essential, just as it was for Chichester, Moitessier and Knox-Johnston. There is no pit-lane to carry out repairs or replenish resources.

Time management in offshore races continues to require robust, accurate timing. Launched in 1992, the Oyster Perpetual Yacht-Master was the first Professional model created by Rolex specifically for yachting. The Yacht-Master’s Oyster case, waterproof to 100 metres (330 feet), features a slightly rounded design to avoid snagging rigging or sails and safely protects the accuracy of the chronometer-grade, self-winding mechanical movement manufactured to withstand the harshest maritime conditions.

Simply completing one of the classic 600-mile races is rightly considered an achievement to celebrate. Marking the significance of the endeavour and the dedication that is required to prevail, historic trophies are awarded to the successful crews. According to John Markos, past Commodore of the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia, one of the prizes has attained legendary notoriety: “The engraving on the back of the Rolex timepiece awarded to the overall winner means everything. It stamps the timepiece with a unique feature that cannot be purchased. While a trophy like the Tattersall Cup is awarded each year, the Rolex watch is personal, owned and carried by the winner. It’s become a recognized symbol of success and achievement.”

In a world where shorter competition formats are becoming ever more popular, it is reassuring that some sports continue to embrace their history and traditions. Promoting and guarding the values of offshore sailing remains a core focus of the organizing yacht clubs involved. The success of their approach is confirmed with new record fleets regularly being established at their races: 362 yachts at the 2017 Rolex Fastnet Race and 130 yachts at the 2018 Rolex Middle Sea Race, for example. The commitment of Rolex is also long-standing, stretching back six decades, but importantly, it is also forward-looking, with multi-year event partnerships in place. The challenge of the open sea is perpetual and, for those willing to take it on and sail in the wake of their heroes, the opportunities to do so are in safe-keeping.

In your comments, please refrain from using offensive language and unnecessary criticism. If you have to be critical, remember – it must be constructive.

0 Comments